Comparative Judgement for Deprivation

Locating deprived regions in developing countries is difficult due to the lack of official statistics and rapidly growing urban populations. To tackle this, we have developed a new comparative judgement method to map areas in developing countries where citizens are deprived or are at risk of gender based violence.

Identifying the most deprived regions of any country or city is key if policy makers are to design successful interventions. However, locating areas with the greatest need is often surprisingly difficult in developing countries. Data collection efforts are impaired by poor physical infrastructures restricting sample sizes. Mass urbanisation can render estimates rapidly out-of-date and a lack of financial transparency in the face of vast informal economies exacerbates the well-established response biases inherent to household surveying. In Africa, according to the World Bank’s chief economist, such issues have generated a statistical tragedy.

Comparative judgement models offer a promising solution. Instead of rating specific areas in the city, we ask citizens to compare different areas based in their deprivation. This removes the need for arbitrary scales of deprivation and avoids asking sensitive questions about specific household incomes.

We collected over 75,000 comparative judgements in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, asking citizens to compare the subwards in the city. From this, we were able to generate the first map of Dar es Salaam that shows deprivation.

We were also able to understand who men and women viewed the city differently, and find areas that women thought were more deprived than the men. This helps in finding areas where women may be at risk of gender based violence.

We extended a popular comparative judgement model, the Bradley Terry model, to include spatial structure. Specifying the form of the spatial structure is difficult, so we instead model the structure nonparametrically. We assumed that the deprivation levels in nearby areas were highly correlated and deprivation levels in opposite parts of the city were not correlated. Incorporating these spatial assumptions allows us to considerably reduce the number of data that needs to be collected in future studies. This makes our method attractive to researchers working in developing countries.

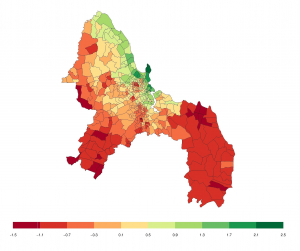

Deprivation levels across Dar es Salaam – the red areas are the most deprived areas and the green areas the least deprived.

We have developed software to both collect and analyse comparative judgement data sets. The python [comparative judgement interface[interface] allows users to set up their own website and collect comparative judgements with ease. The results can the be exported and analysed using our [BSBT R package][R]

We are able to estimate the relative deprivation of every part of Dar es Salaam. e see a north-south trend, whereby the level of deprivation increases further south in the city. We find several sharp changes in deprivation in the city centre, where slums neighbour affluent subwards. The most affluent subward is Masaki, and the ten most affluent areas are all concentrated around the Masaki peninsula directly north of the city centre and home to most of the affluent expatriate communities. The ten most deprived subwards are geographically spread out, with one, Mpakani, being located in the centre of Dar es Salaam and the others spread across the outer regions of the city. Four of the ten most deprived subwards are in the Somangila ward, a coastal ward in the east of the city.

The Bayesian Spatial Bradley-Terry Model: Urban Deprivation Modelling in Tanzania

Identifying the most deprived regions of any country or city is key if policy makers are to design successful interventions. However, locating areas with the greatest need is often surprisingly challenging in developing countries. Due to the logistical challenges of traditional household surveying, official statistics can be slow to be updated; estimates that exist can be coarse [more]